This week, we get angry at the late 1990s record industry. Like usual.

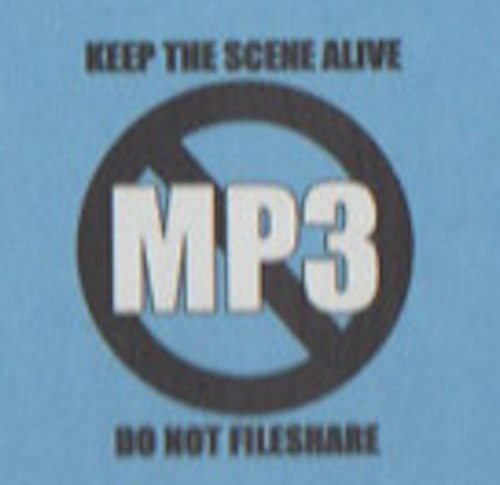

I was downloading cover art for a makina record I had Soulseeked the other day when I noticed something kinda funny on the label:

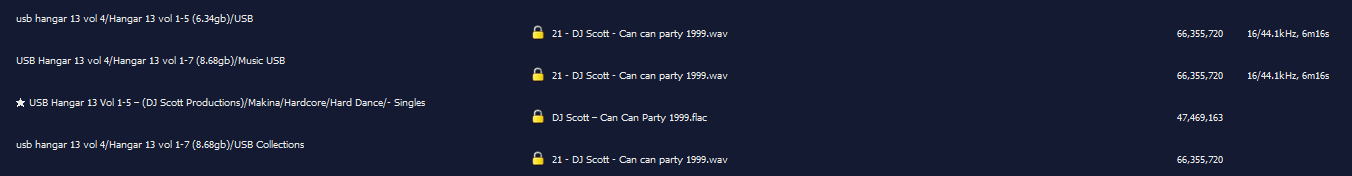

It was actually Volume 7 but I’m not subjecting you to that crime against image resolution.

Do you see it? Here, let me zoom in:

If you’re not really familiar with makina, this is funny because perhaps no hardcore scene has ever died quite as hard as the UK makina scene did. Hardcore music is inherently fluid; producers come and go in all styles, yes, but when one genre dies, it’s very common to see artists working in it to simply move on to something new. When the last dregs of breakbeat hardcore dried up, the artists still working in that space simply moved onto newer styles of happy hardcore. When gabba was killed by about a thousand different things, all of its biggest proponents kept making nu style/mainstream or industrial hardcore or speedcore or darkcore or any other of the thousand or so adjacent sounds that took its place. This sense of continuity keeps genres alive, ironically; you can go on Soulseek right now and find a half dozen uploads of, I dunno, Sperminator, even if that style of music hasn’t been prominent for 30 years. These records are loved, but also diligently archived and kept alive by people who have put a lot of effort into making sure this music outlives the structures that it was designed for.

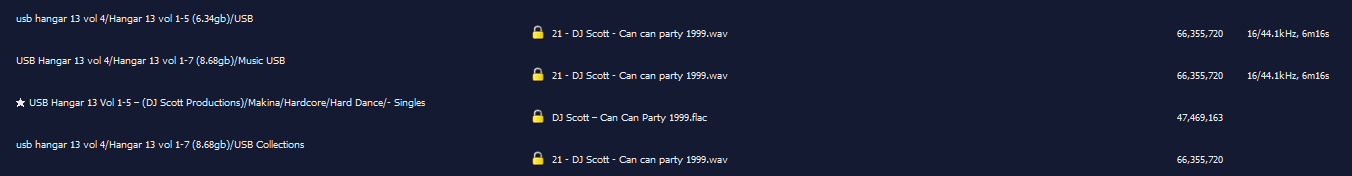

But while certain aspects of UK makina - the rapid-fire MCing, the vague idea of the sound, the youth culture - survived the late 2000s collapse of the genre through ancient YouTube videos and memes (albeit usually known to people who have no idea what makina is and have never listened to more than 30 seconds of it in their life), the music itself is dangerously obscure and suffers from almost no preservation effort. More than half the discography of DJ Scott, the man generally considered primarily responsible for introducing makina to the UK and making it such a sensation in Northern England and Scotland, is impossible to find consistently in good quality online. You can, of course, hit the secondary market, but vinyl is and will continue to be a dying format in the EDM world. Not only is it harder and harder to find classic makina 12”s on sale, but the very act of relying on an analog format to keep your legacy content alive is something almost no other notable style with a rave-era background does, and for good reason.

This column might well be considered my love letter to the experience of listening to hardcore through awful-sounding web streaming sources but this is a bit far even for me.

I’m a data hoarder. I have over a terabyte of mp3s. I know not everyone is going to be so zealously committed to the idea of everyone having a digital copy of everything they listen to. But I don’t think I need to explain how keeping music available on P2P services like Soulseek or sites like archive.org, things that let you not only listen to something but keep it in circulation by having your own copy, is a necessity for scenes like this.

The underlying problem is that the record industry spent a LOT of money in the early 2000s convincing people that music piracy was killing the viability of music as a career. And a lot of people believed them! To this day, a lot of people genuinely believe that music piracy singlehandedly placed your favorite bands in a precarious economic position, despite repeated evidence that music piracy has little significant effect on music sales. Of course, the point was never actually to help musicians - it was about control, something that the music industry had lost for the first time in its hundred year history, and the factors that have been killing the viability of music as a career have nothing to do with piracy and everything to do with an acceleration of capitalism that would require killing the music industry to reverse - but the ideology nevertheless became deeply entrenched amongst musicians, who did the dirty work of shaming listeners so that labels, who had universally worse reputations amongst the general populace, didn’t have to.

You’d think that this argument would have passed up the dregs of the rave community, which had never been consistently profitable in the first place and was often inherently anticapitalist by multiple metrics even when it wasn’t explicitly political, but the sanctity of copyright took hold amongst DJs almost as easily as ecstasy amongst disaffected European youth; people who had spent years making music that gleefully sampled without regard for permission and had grown up in an environment of pirate radio and Walkman cassette bootlegs now fundamentally believed that filesharing was killing the culture, as if piracy of all things had somehow caused rave music to become commercialized megaclub music and the free party community to get effectively outlawed.

Whatever the case, the music industry won and now we only really care about filesharing as a vector for inane DJ drama. I think that people are beginning to come back around on the “piracy is a moral imperative” train now that we all live in a world where art that we love can be made entirely inaccessible by legal means at a moment’s notice and legally consuming media is only very marginally less of a pain in the ass than it was 20 years ago, but it can be argued that the ship has already sailed for a genre like makina. It still exists - in large part thanks to the efforts of Monta Musica, who have pretty much singlehandedly kept it alive in the UK - but the music of its golden age may be doomed to forever be hard to find, at least without a much broader effort to archive it and make it easier to listen to. I honestly worry even more about today’s music, because modern EDM fans are happy to simply stream their favorite songs forever and never own a copy, legally or otherwise. I’ve already seen tracks I used to listen to regularly disappear into the aether, probably permanently, because the rights got fucked up or the label shut down or the artist just didn’t feel like keeping it accessible. The edge case of the 2000s UK makina scene may someday become the default for any relatively niche sound.

If you love this music, do it a favor and rip whatever CDs you have. If you’ve got a decent vinyl setup, digitize your records. Record your tapes. Find digital downloads of songs you stream. Not everybody has the means or desire to fill hundreds of gigabytes of storage space with music or share their collection to the masses, but if we were all a little more conscious of how transient the way we consume music is then maybe we wouldn’t have to see a beloved regional dance music tradition like makina become endangered through its own machinations.

The Breakdown is a biweekly column about hardcore, breakcore, and jungle written by Georgia Ginsburg. Encompassing reviews, essays, retrospectives, and more, it seeks to chronicle the harder end of the rave era and the lasting cultural impact it had on dance music.