This week on The Breakdown we take a deeper look at Lolita Storm, one of the stranger and more fondly remembered acts of the first era of digital hardcore, and attempt to disentangle their strange existence as as a group thrust into the vanguard of feminist punk despite having no desire to be a part of it.

Content Warning: This article contains discussion of music with strong sexual and kink themes.

The first song on Lolita Storm’s seminal 2000 record Girls Fucking Shit Up is about sneaking off into the toilets at a club to have a shag. The Brighton-based quartet could not be called many things; they weren’t sophisticated, they weren’t complex, they weren’t feminist (despite having been signed to Digital Hardcore Recordings’ explicitly feminist Fatal sublabel) or even political, and they certainly weren’t popular in their hometown. What they were, no matter what direction they went, was deeply, irreverently, uncompromisingly horny - and gleefully stupid on top of it - to the point where it wraps right back around into pure comedy. Lolita Storm’s music is often sold as a Riot Grrrl take on the raucous sound of early DHR in retrospect, probably because if the average person hears the words “Riot Grrrl digital hardcore” there’s a 90% chance they’re going to go “oh fuck yes” and listen. This has the beneficial effect of causing people to listen to good music, so you can’t really fault the technique, but while Lolita Storm did indulge in the frank sexuality and aggressive girl-forward performance practices of Riot Grrrl, they were a much stranger group than that; one whose aspirations were more 70s and Sex Pistols than 90s and Bratmobile, and one worth remembering in greater detail.

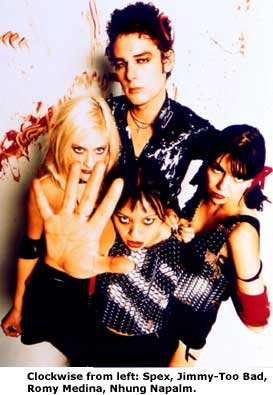

The very first thing Lolita Storm did, before they even developed a relationship with the label they would become eternally associated with, was establish their entire sound and aesthetic to a T. 1999’s Goodbye America / Get Back (I’m Evil) 7” (released a mere 7 months after they first formed) features all the hallmarks of their sound: its formula of slightly sparser break-forward sections with chanted vocals alternating with ultra-loud choruses flanked by blasting punk samples and singalong melodic lines, a tongue-in-cheek feminine image that is simultaneously ultradominant and ultrasubmissive, and a haphazard approach to musicianship where songs rarely break the 2 minute barrier and the band’s three vocalists - Spex, Nhung Napalm, and Romy Medina - all just kinda wail in unison.

It makes sense that Lolita Storm hit the ground running because there was an implicit understanding from the moment that the band started that they would be style-before-substance. “We just sort of put ourselves together ’cause we all looked really cool and stuff. So we said 'Hey, let’s get a band together, and we’ll call ourselves Lolita Storm,'” says Spex in an interview with Rockbites that serves as one of two remaining easily accessible insights into the band’s ethos. There is a real argument to be made that the band’s hypersexualized image, with songs about BDSM and ramshackle costumes that made them look like “futuristic prostitutes” and discounts on entry to their club night for people who showed up in particularly slutty outfits, was much more important to the Lolita Storm experience than the music itself. This is by design - Lolita Storm was in part founded because Spex and actual instrumental producer Jimmy Too-Bad were previously in a “really, really shit” indie band and decided they hated indie music so much they were going to start making music expressly to piss off people in the Brighton scene - but also does a bit of a disservice to how intoxicating it is to listen to a Lolita Storm record.

Lolita Storm’s DHR debut, Girls Fucking Shit Up, is an oldschool punk record in every sense but instrumental. Like any good punk rock record, it packs 15 tracks but only weighs in at a scant 25 minutes; like most early punk records, it also contains about 15 copies of the same exact song. The formula that they established on their debut single remains true here and is only really broken up by the wider variety of samples that introduce some of the songs. In the hands of a less interesting group, this would make GFSU a pretty underwhelming listen; Lolita Storm has never been called “uninteresting” and probably never will. Lyrical topics vary little from the aforementioned dingy sex anthems and tongue-in-cheek kink exploration, but some time is dedicated to send-ups of UK pop culture icons like Sid Vicious (“O.K. Sid) and Anthea Turner (“Anthea Turner’s Tears”), and they even manage to set aside a couple minutes to talk about the benefits of stimulant abuse (“I Luv Speed,” and a running theme in their brief career; one of my favorite Lolita Storm anecdotes is the time they put a VICE interview briefly on hold so the interviewer could source them some American cocaine to try, which at that point was very difficult to find in the UK).

GFSU’s fairly unanimous standout track is “Red Hot Riding Hood,” which features the catchiest of the album’s many great choruses and the dreadfully earwormy “I’m not afraid of the big bad wolf” chant. Personally, I also have a particular fondness for the simple refrain of “Slave Boy” and the slinky guitars of “He’s So Bad I Luv Him,” but the album is a rollercoaster from front to back and never ceases to express a sense of overwhelming, highly adolescent fun. Perhaps its most oldschool punk trait, especially when comparing to the aforementioned Sid Vicious’s Sex Pistols, is how averse it is to taking its revolutionary paintjob seriously. Punk has never been uniformly political or non-political but it has always played with the aesthetics of politics; a band like the Pistols may have looked similar to a legitimately political band like The Clash, but merely appropriated leftist terminology and aesthetics while themselves being ideologically hollow and entirely focused on provocation. It can be easily argued that Lolita Storm does the same thing, taking a lot of influence from the general imagery and focus on sexuality of Riot Grrrl but never coming close to legitimately espousing feminist rhetoric or reclaiming sexual power in a political way.

I find it hard, however, to view Lolita Storm’s lack of meaningful rebellion anywhere near as cynically as I do the aesthetics of the Sex Pistols. This is largely because, unlike the Pistols, Lolita Storm weren’t in it for the money. They weren’t a product of the industry and their image wasn’t at all calculated; even in interviews where they were asked about feminism, while they would pretty much always deny being a feminist band, the reasoning was always complex and non-uniform. I get the sense that it was less that Lolita Storm were uninterested in the general ethos of feminism and more that they felt held down by being associated with how active and conscious it was as a movement. Would Lolita Storm’s music be better if it was more politically savvy? Maybe. But at the same time, the youthfulness and omnidirectional revolt against good sense is the point of it all. Is it tasteless when they turn the death of actress Natalie Wood into a sailor song where they cheekily urge her to “swim” and “don’t be dragged under” over raucous, morphing beatwork? Yes, absolutely. Does that mean that it’s not also a darkly hilarious singalong and the best thing they released after GFSU? Probably not. Lolita Storm’s primary image in retrospect is not one of calculated, performative subversion but of young women just trying to have fun and make the most challenging music they could think of because the UK was and continues to be depressing to live in and the only excitement they found in art came from weirdos hundreds of miles away in Germany.

And it’s not like they weren’t meaningfully rebelling against anything. Lolita Storm were actually very willing to talk about their beliefs. They thought art should be about “pioneering” and have “no restrictions and no rules.” They thought rock music was creatively dead and only through computers could it find salvation - “guitar music didn’t have anywhere to go after the ’70s, so all good music has to be done electronic nowadays,” says Jimmy Too-Bad in the Rockbites interview - but that rave music was boring and the spirit of rock & roll, of artists “like Elvis and Chuck Berry,” was still something to strive for. Not deep ideals, sure, which is to be expected of artists who came from means and fell into (weird, leftfield, underground) stardom by means of boredom rather than by having real problems. But the spirit does exist, and the music they made transcends the circumstances of its creation.

Lolita Storm postured as though they were a classic punk band but they existed in a very different time, and so when it came time for the band to finally close up shop it fell apart not in a bang of dramatic life-altering theatrics but with a slow, boring, uneventful whimper. 2001’s Sick Slits E.P. didn’t make nearly the same impact as their album a year before had and marked the end of their relationship with Digital Hardcore Recording; it took them another two years to put out new material afterwards, by which point DHR was a dwindling label mostly putting out owner Alec Empire’s solo material, and 2003’s Studio 666 Smack Addict Commandos landed on Arizona indie/electronic label 555 Recordings. Lolita Storm had started on an indie label - the short-lived Rabid Badger imprint of London indie staple Fierce Panda Records - and, in the end, they ended up on one too. In an act of tragic cosmic comedy, the band that had started like entirely as a “fuck you” to the Brighton indie scene made the the evolution from firebrand digi-punks to a twee electro-indie outfit at the ripe old age of, uh, 6 years. A true innovation of speed in the tradition of punk bands giving up and making something completely different in old age. 2004’s Dancing With The Ibiza Dogs was both their first and last multi-track foray into the indie sound and, with the exception of a cover of Nick Cave’s “Stranger Than Kindness” contributed to Failure To Communicate Records’ 2006 Eye For An Eye tribute album, Lolita Storm’s last release too.

In the years since, Lolita Storm has gained a cult following through rediscovery via RateYourMusic and the long-needed redistribution of the band’s music on streaming services (I even managed to find a random high school that gave it a 10/10 review on their news site last year, for some reason). There’s something charming about a band created by a bunch of bored young people being found again by bored young people two decades later and championed as a standout of early digital hardcore and breakcore. Lolita Storm’s music wasn’t sophisticated, or complex, or feminist, or even political, and it certainly didn't make them big in their hometown, but it speaks to a youthful exuberance that never dies. Their career was brief, their catalogue only barely more than 30 songs deep, and their revolutionary spirit not nearly as conscious as it looked at first glance, but GFSU still brings a smile to my face every time I spin it and I can’t imagine a world where it doesn’t resonate with others.